The UK’s ambition to become a major centre of EV battery manufacture is one step closer as work begins on its first integrated lithium-ion battery recycling and refining facility that is capable of producing the key ingredients of battery cells on an industrial scale.

The new plant in Plymouth is the penultimate stage in British company Altilium’s four-part plan, which will culminate in the creation of a refinery on Teesside. When it goes live at the end of 2027, this is slated to produce highquality, recycled cathode active material (CAM) for UK gigafactories.

Until then, the Plymouth plant will produce recycled nickel mixed hydroxide precipitate (MHP) and lithium sulphate – critical intermediate materials for domestic production of battery cathodes used by a range of industries.

Creating the CAM used in EV batteries requires expensive refining. Efforts in this direction have been boosted by rules governing new EV batteries sold in the EU that state they will need to have minimum levels of recycled lithium, nickel and cobalt from 2031, with further increases in 2036.

Altilium has developed a process for extracting and processing these metals to the required quality and earlier this year announced it had produced, at the UK Battery Industrialisation Centre, the UK’s first EV battery cells using recycled CAM and complying with those regulations.

Why domestic battery recycling is 'vital'

The news comes in the wake of a report by the government on battery recycling in the UK. It says a secure supply of critical minerals – such as lithium and cobalt – is vital for economic growth and security. However, the country is currently reliant on the international market, especially China, to supply most of these minerals.

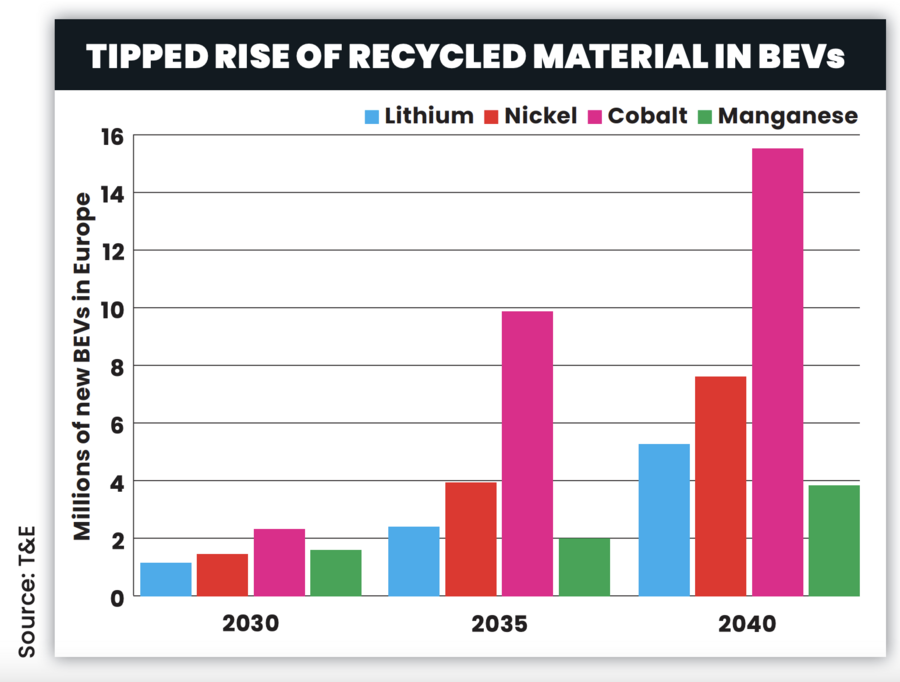

One solution, it says, lies in the recycling of lithium ion batteries from the growing volume of endof-life EVs, which, it claims, “could supply between 39% and 57% of the demand for lithium, cobalt and nickel by 2040”.

However, the cost of such work can be prohibitive. Altilium says its approach underlines the sector’s fi nely balanced economics. “We’re always looking to optimise our processes to make them cost-effective,” said Altilium spokesperson Dominic Schreiber. “We’re scaling progressively and, crucially, validating everything to ensure we de-risk the business at every stage. Until our Teesside plant comes on stream, our intermediate material will be a necessary income generator.”

When that day dawns, Altilium’s customers for its Teesside product are likely to include Nissan’s current and forthcoming gigafactories in Sunderland and JLR owner Tata’s site in Somerset.

“For car and battery makers keen to reduce their carbon footprint as well as meet the new EU battery regulations, it won’t make sense to ship in material from elsewhere,” said Schreiber. “The battery is an EV’s biggest single source of embedded carbon. One with CAM made from recycled metals has up to 74% fewer embedded emissions.”

Altilium uses a third-party supplier to handle the first stage of its recycling process. This involves shredding used batteries and extracting their crucial metals in the form of a powder called black mass, which Altilium then refines.

Join the debate

Add your comment