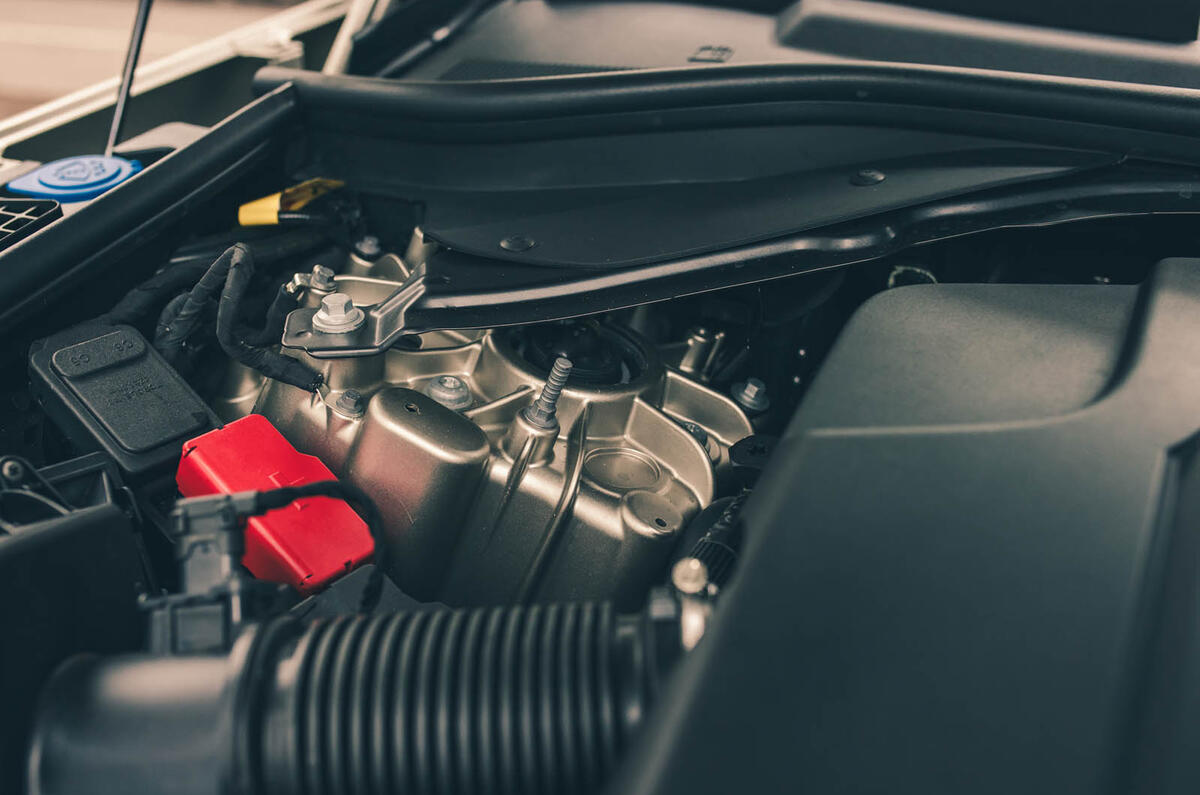

The pick of the engines remains Range Rover's Ingenium six-cylinder diesel. In D350 trim it delivers 345bhp and 516lb ft, yet in normal driving you barely know it’s switched on.

Even when you ask a lot of this powertrain – and a fully fuelled weight of 2667kg as tested means you might need to – it’s smooth and unobtrusive.

From rest, two-up and fully gassed, it went from 0-60mph in 6.3sec – a little off the claim but a number that still means it’s a fast and capable machine. A smoothly responsive one too, with easily selectable gear ratios if you opt to use the gearshift paddles yourself, and a long throttle travel with predictable kickdown if you choose to let the gearbox software do it for you.

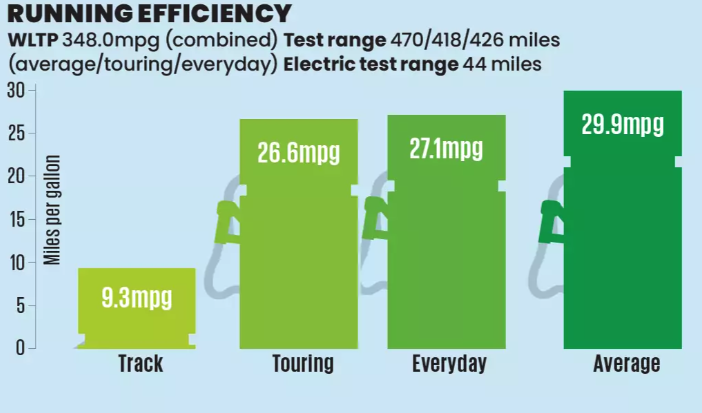

In more relaxed driving, this is one of those cars where it’s usually unnoticeable which gear it’s adopting, and while there’s only so much the best software and hardware in the world can do about the fuel consumption of a car of this size, it does its best, adopting as high a gear as sensible without labouring the engine or harming the refinement. At a 70mph cruise, an eighth-gear ratio that means the engine is spinning over at just 1550rpm keeps it particularly unobtrusive.

The PHEVs are responsive and when the 3.0 petrol engine is zinging along, it’s doing it very quietly in the background, with just a little sporting edge to it. Things are more responsive if you pull the gearlever into ‘S’ rather than ‘D’ but the electric motor is there to assist anyway – you can just use throttle rather than have to pull gears to make progress.

In reality, petrol straight-six PHEV grunt suits the Range Rover rather well, particularly if you have an unapologetically lavish example on your hands – as our wood-trimmed, light-leathered Autobiography car was.

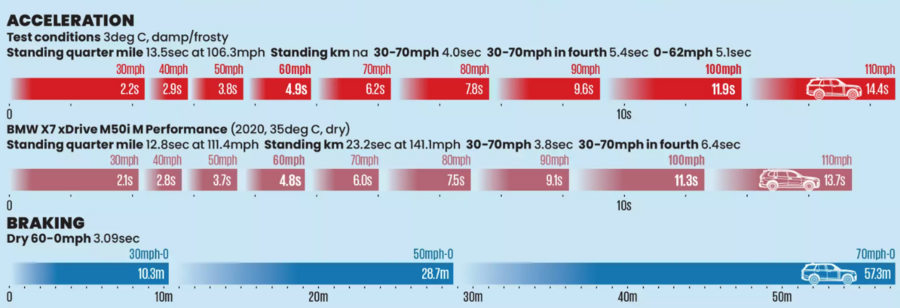

For one thing, the level of performance on offer is more than adequate. A recorded 0-60mph time of less than five seconds is strong given the car’s near three-tonne mass, and 11.9sec to 100mph means the medium-rare P550e only slightly trails the red-hot, carbonfibre-bonneted and deafeningly loud Range Rover Sport SVR of 2015.

The nature of the performance is more compelling still. The car starts up in EV mode whenever possible

and moves off the mark with a grace you don’t initially expect, and the powertrain will continue to operate

in zero-emission fashion for as long as there is charge in the battery and nothing more than modest

acceleration is asked for. While not quick in its pure-electric mode, as an EV the P550e gives a measured, polite account of itself that bodes well for the upcoming electric Range Rover proper.

When it does come on song with a distant nasal thrum, the 3.0-litre petrol six is rather a lovely companion. Its initial response is artificially enhanced by the 215bhp electric motor, especially at low crank speeds, but the calibration of the two power sources is slick, with electric force then tapering as the engine hits its sweet spot.

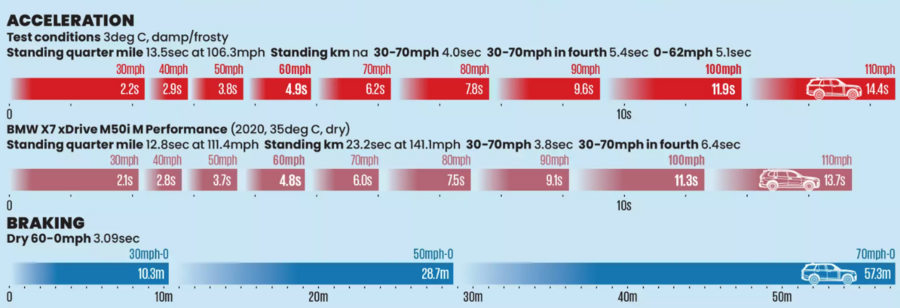

This is an intuitive powertrain, with a precision that makes the driving experience just a touch simpler. The P550's acceleration and braking figures can be seen below.

Meanwhile, the BMW-sourced V8 petrol engine perhaps suits the Range Rover even better still and is a deserving and indulgent fit for the flagship models. There’s a faint woofle at low speeds, building to a cultured growl under harder loads and at higher revs. It's available in a couple of different outputs but either one is brisk. The V8 is unstressed, even when pulling out to overtake slow-moving traffic on an A-road. At times, though, the V8 can feel a touch too involved. It is particularly tricky to judge throttle modulation. Under acceleration it just wants to give it the full beans, whereas the typical Range Rover driver may want a more refined, dignified take-off from a set of traffic lights.

Braking is in general a touch less impressive than the engines. Unfortunately, the test track never quite managed to dry out during our day at Millbrook, so we had to deal with some damp patches. Even so, a 60-0mph time of 3.67sec for the D350 and a 70-0mph distance of 66.2m were poor.