Like cursed penguins, a whole barrage of helicopter designs has failed to make it.

From advanced stealth helicopters that cost billions, to sleek gunships and vast flying cranes that proved too much, many promising designs never made it. Here is a celebration of some magnificent rotorcraft that have been relegated to obscurity in the scrapheap of aviation history:

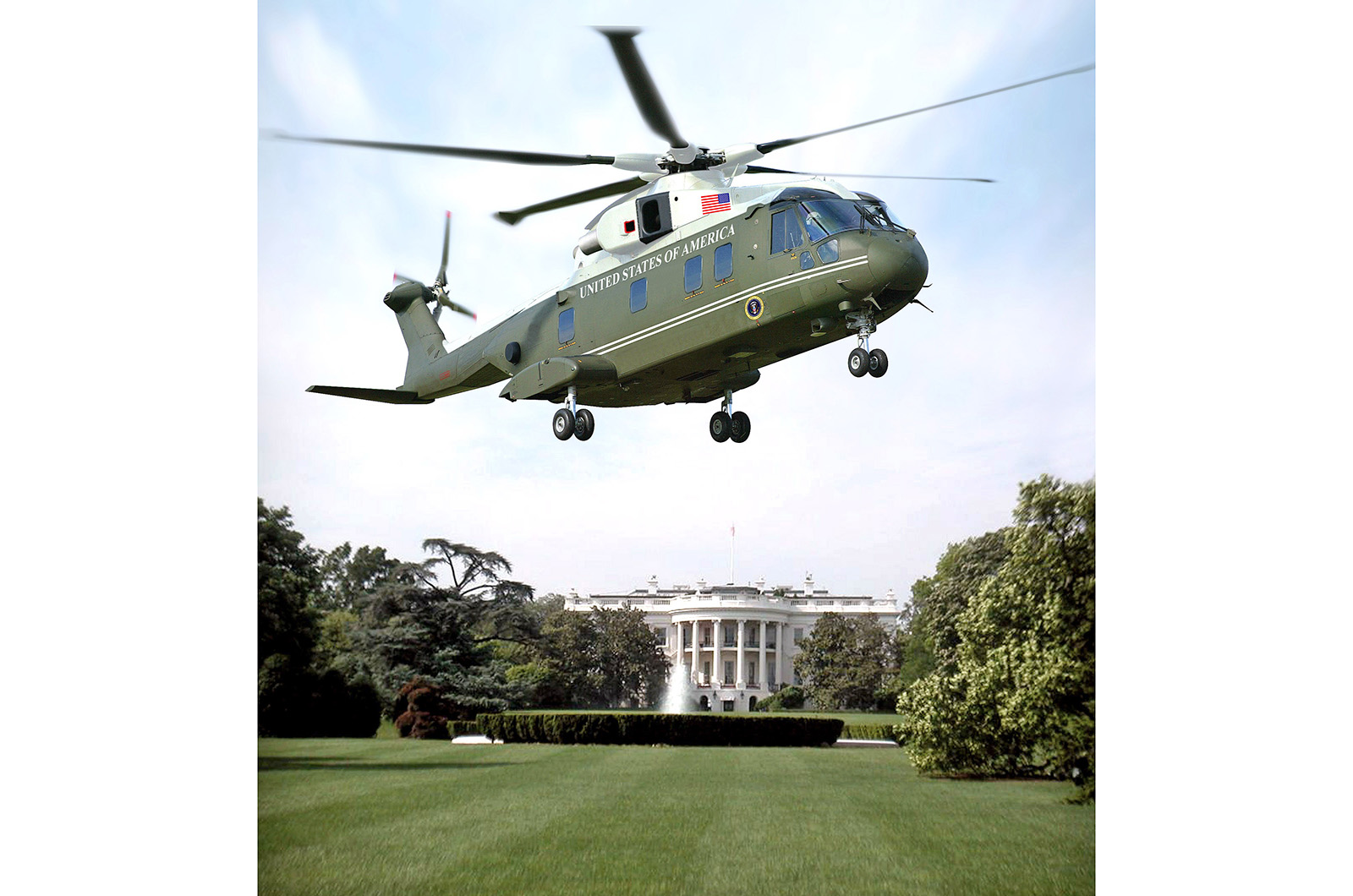

11: Lockheed Martin VH-71 Kestrel

Originally envisioned as a state-of-the-art replacement for the ageing Marine One fleet, the VH-71 Kestrel was an ambitious military adaptation of the AgustaWestland (now Leonardo) AW101 Merlin. With its tri-national industrial pedigree, the aircraft promised range, capacity, and cutting-edge communications — it would have been a 'flying White House' tailored for the President of the United States.

Led by Lockheed Martin, with AgustaWestland and Bell Helicopter in support, the project was intended to deliver 28 helicopters. But as new security and communication demands emerged, requirements ballooned. Design revisions followed. With each one, costs climbed, and delays lengthened.

11: Lockheed Martin VH-71 Kestrel

By 2009, after nine aircraft had been delivered in a preliminary configuration and a whopping $4.4 billion already spent, the programme was axed. The projected total cost had soared to over $13 billion — a colossal figure deemed politically indefensible amid budgetary scrutiny after the 2008 global financial crisis. President Obama's administration pulled the plug entirely.

The airframes, no longer presidential, were quietly sold to Canada at a steep discount and repurposed for spare parts. The VH-71's collapse stands as a cautionary tale in modern defence procurement — not of technological failure, but of overreach, shifting goals, and the perils of adapting off-the-shelf designs for the world's most demanding mission.

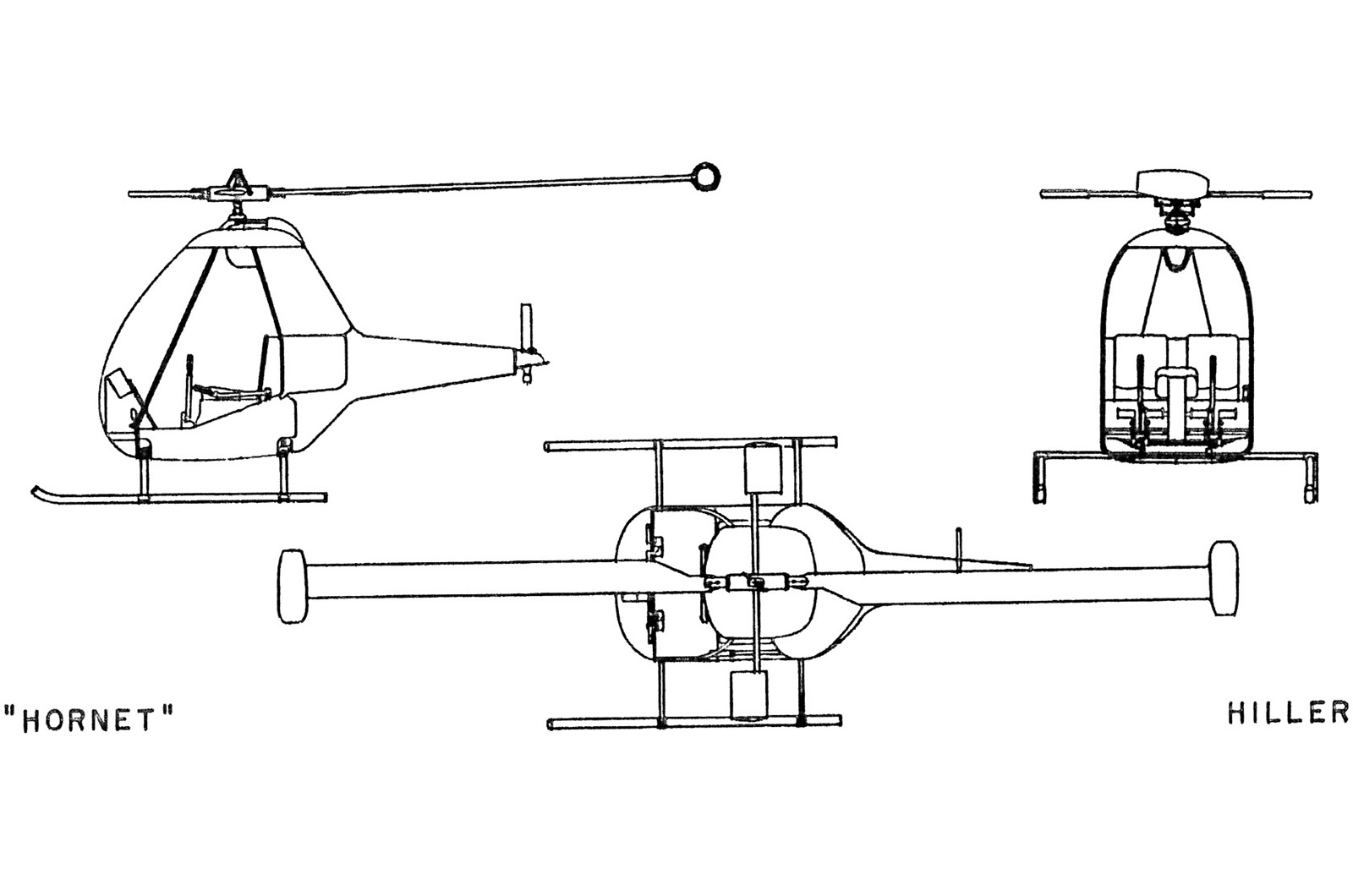

9: Hiller YH-32

The rather quaint Hiller YH-32 Hornet, originally designated HJ-1, was an experimental ultralight helicopter developed in the United States during the early 1950s. It was powered by two ramjet engines mounted on the rotor tips, each producing 45 horsepower. This innovative design eliminated the need for a conventional tail rotor.

Work began in 1948, following earlier jet rotor experiments like the XH-26 Jet Jeep. Although mechanically simple, the Hornet suffered from major issues. The ramjets suffered from high fuel consumption, and it had a limited range. The helicopter was also extremely noisy, and autorotation proved difficult in a power failure.

Add your comment