Try going for a run, or even a couple of trips upstairs, wearing a 30kg backpack and it soon becomes obvious how much hard work it takes to lug that extra weight around.

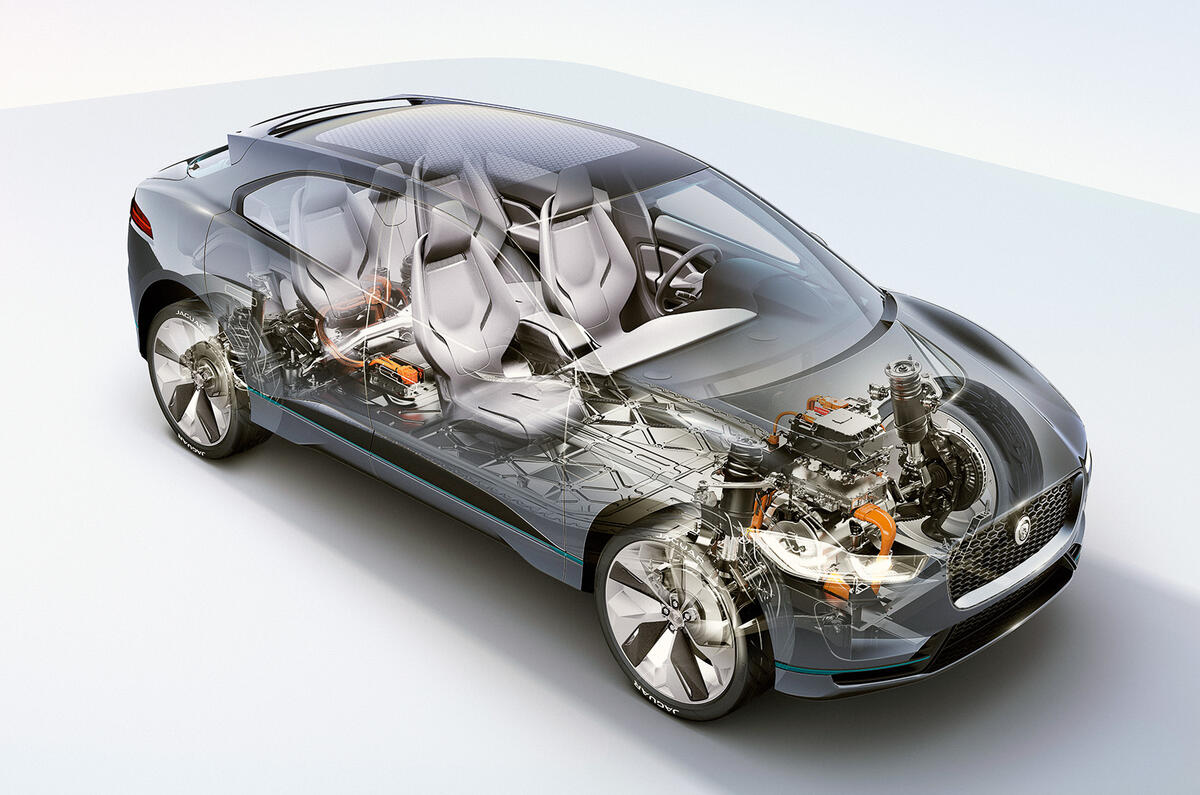

Lightweight technology is even more pressing with the rise of EVs, as the multiple-award-winning Jaguar I-Pace demonstrates. It makes no sense to build an EV with a heavier steel chassis and body and then compensate for that weight with a bigger, heavier battery.

As far as fuel consumption goes, a lighter car needs less energy to move it: it’s as simple as that. Pushing a classic Mini on your own is easy but moving a full-sized SUV solo is anything but. So manufacturers are always looking to reduce weight or at least reduce the weight spiral, mainly by using lightweight steel and aluminium alloy in the body construction. Although far cheaper than carbonfibre, aluminium construction is expensive, partly because of the material itself and partly because of the construction methods. That’s why it only appears to any great extent in premium cars.

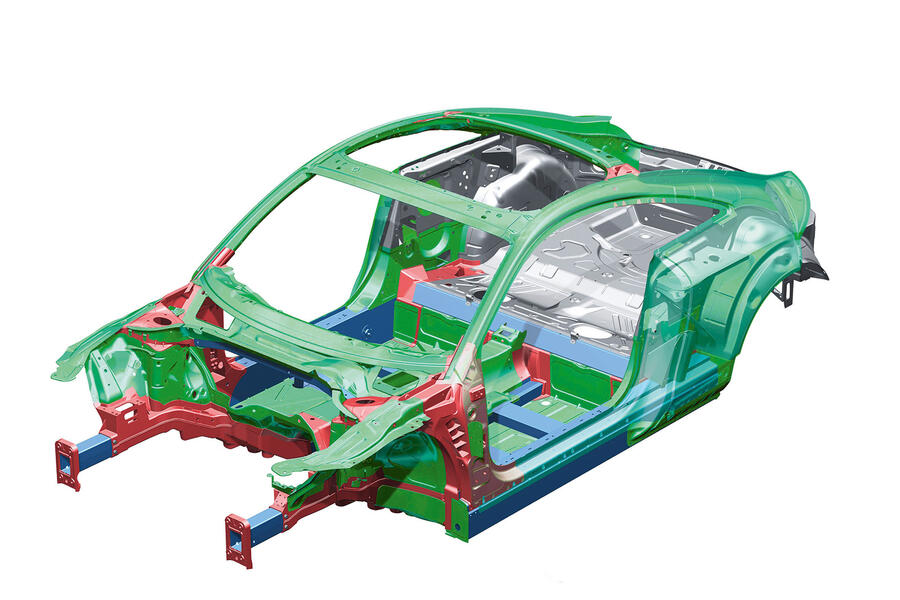

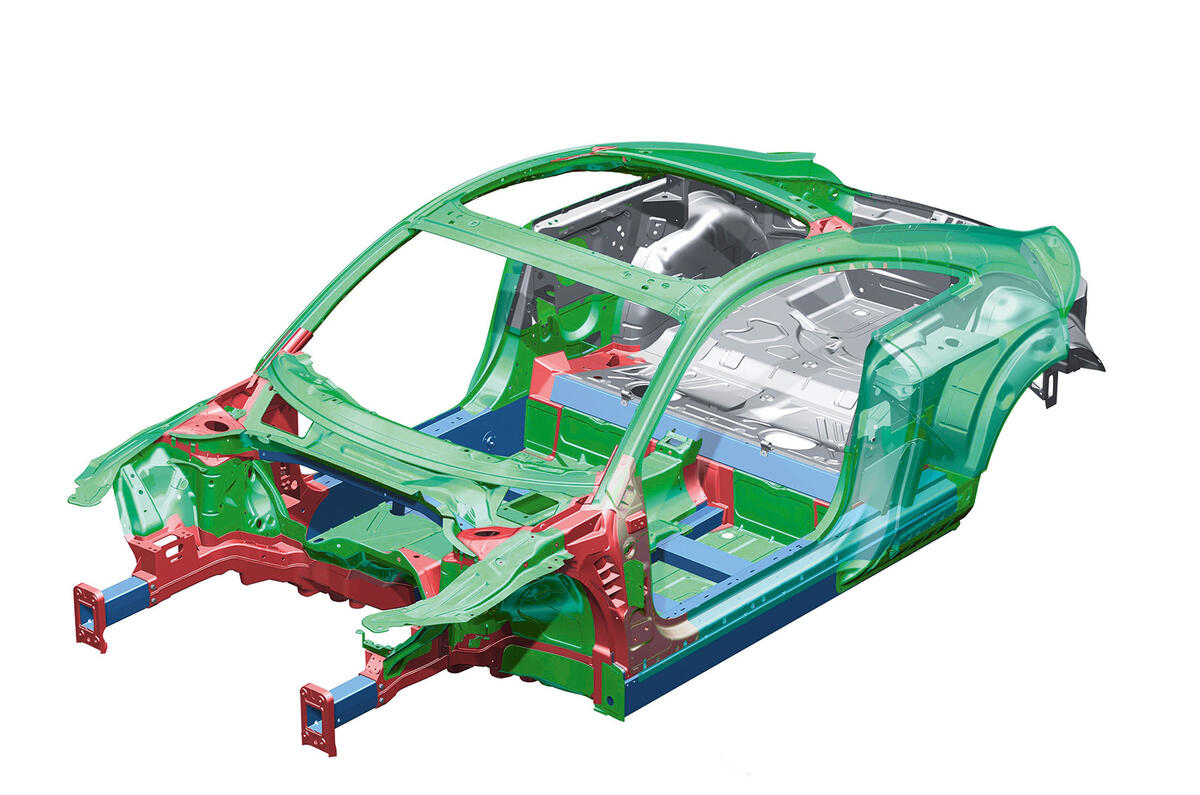

Steel is a relatively easy material to work with and panels can be pressed and folded with crisp, sharp edges. Aluminium panels are less amenable to sharp folds, and if the radii on a swage line are too small or a shape too intricate, the material can crack. Designers and engineers have to work more closely to achieve the shapes designers want.

Joining the stuff together gets trickier as well. Whereas manufacturers have been joining steel for decades using MIG or spot welding, bolting and, to a lesser extent, riveting, some different methods are needed for aluminium. A favourite for joining panels is bonding (gluing) and riveting using self-piercing rivets. A conventional rivet is pushed through a drilled hole and bashed over, but self-piercing rivets push through the first layer of aluminium without drilling and splay out into a second layer but without piercing it. In cross-section, it resembles a wisdom tooth with those large roots and once in, like the tooth, it doesn’t want to come out.

A tricky aspect of mixing steel and aluminium is the possible effect of galvanic corrosion between the steel and aluminium, a battle that the aluminium generally loses and causes it to fall apart. That means adding some protection apart from the glue and, for example, Volkswagen uses a purpose-designed lacquer on the two surfaces to keep them apart by a whisker – even though they’re joined.

Reducing the weight comes not just from the intrinsic weight of the material but also from its strength. Modern aluminium alloy body structures use a mix of different types of alloy and using a higher-strength grade for some body panels means they can be thinner and even lighter, creating a virtuous circle.

Don’t ever expect to see a car made in pure aluminium, though: it’s too soft. An aluminium alloy contains a trace of other materials such as silicon and magnesium. It’s clever stuff and why, in some respects, car making today is more about what happens in a chemistry laboratory and a little less about spannering.

Join the debate

Add your comment

It’s not the material you use ...

... it’s the detail of the design that makes it work. Optimising the design to balance the many, many NVH and Crash load cases to achieve an optimum design. You can get light cars made of steel and heavy cars made of aluminium.

Good to see a rare picture of a body-in-white in Autocar plus a bit of technical discussion.

But please, don’t ever say lightweight steel. Steel is steel. There isn’t a lighter weight version of steel. All steel has the same density and the same stiffness but you can get many different grades of strength.

Ha Ha

Ha Ha

As soon as I saw the picture of the I-Pace, I made a guess that someone would claim this was a paid advertisement.

Very interesting article though.

Lightweight construction more important?

With EVs, I think that you could argue that lightweight construction is now less important than it used to be. With such heavy batteries needed to achieve a long range, the difference in performance and efficiency between a steel bodied and an aluminium car is less than it used to be. So arguably an extra 100kg of body weight really isn't going to make much difference.

Also, all EVs have energy recovery under braking, reducing the efficiency advantage of a lightweight car. So the fuel consumption and range advantage of weight reduction isn't as big as it would be for a combustion engine model.

Much as I like the idea of lighter weight vehicles, I think the premise that aluminium construction is becoming more necessary has more to do with JLR's publicity for this technology than any real truth in the matter.

LP in Brighton wrote:

Yep. Not much to be gained by saving 100 kg when your car weighs 2,000+ kg.