Thierry Neuville has a penchant for getting four wheels off the ground. Earlier this year Hyundai’s World Rally Championship driver achieved the longest-ever jump at the famous Colin’s Crest in Sweden, flying 44m through the air and smashing Ken Block’s 37m record from 2011 in the process.

It’s often the money-shot of a rally stage, but behind the spectacle of a jump there is a precise science that relies on perfect synchronisation between driver, co-driver and machine.

Talking to Neuville in Finland, where he’s testing for the 2016 season, the secret to his Colin’s Crest success sounds fairly simple: “I stayed flat on the throttle”.

But the Belgian explains there’s a lot more to it than a heavy right foot, and not every jump allows a hell-for-leather flat-out approach at 120mph.

Indeed, Neuville describes how each jump has its own characteristics, and the greatest challenge is what comes before and after it; the approach and landing are key to the jump’s success.

“As soon as you brake the car goes down on its dampers,” Neuville explains. “When you get up to the crest and release the brakes the car comes out of the dampers and the springs push the car up as you take off, so you get a really big jump.

“But you’re not aiming for this, you don’t want the highest jump,” he warns. “You have to be very careful to be off the brakes before you jump. This is the main thing, if not you can have high jumps that lose you time.

“Don’t brake too late, and don’t brake too early,” he emphasises.

Slower jumps and crests are taken in gears two to four, and the rule of thumb for them is simple: the less time your wheels are in the air, the faster you go. That’s because you need to get traction back as fast as possible to pick up speed again. But for the fast jumps that are tackled in sixth gear, you need to be low and you need to be fast, and well-timed braking is still crucial on landing.

One of the many dangers is damaging the front of the car. “If the nose is pointing down in the air you can land on the front and damage the radiator,” he says.

“If you keep on the brake as soon as you lift off the throttle and take off, the front goes down and you will hit the nose when you land.

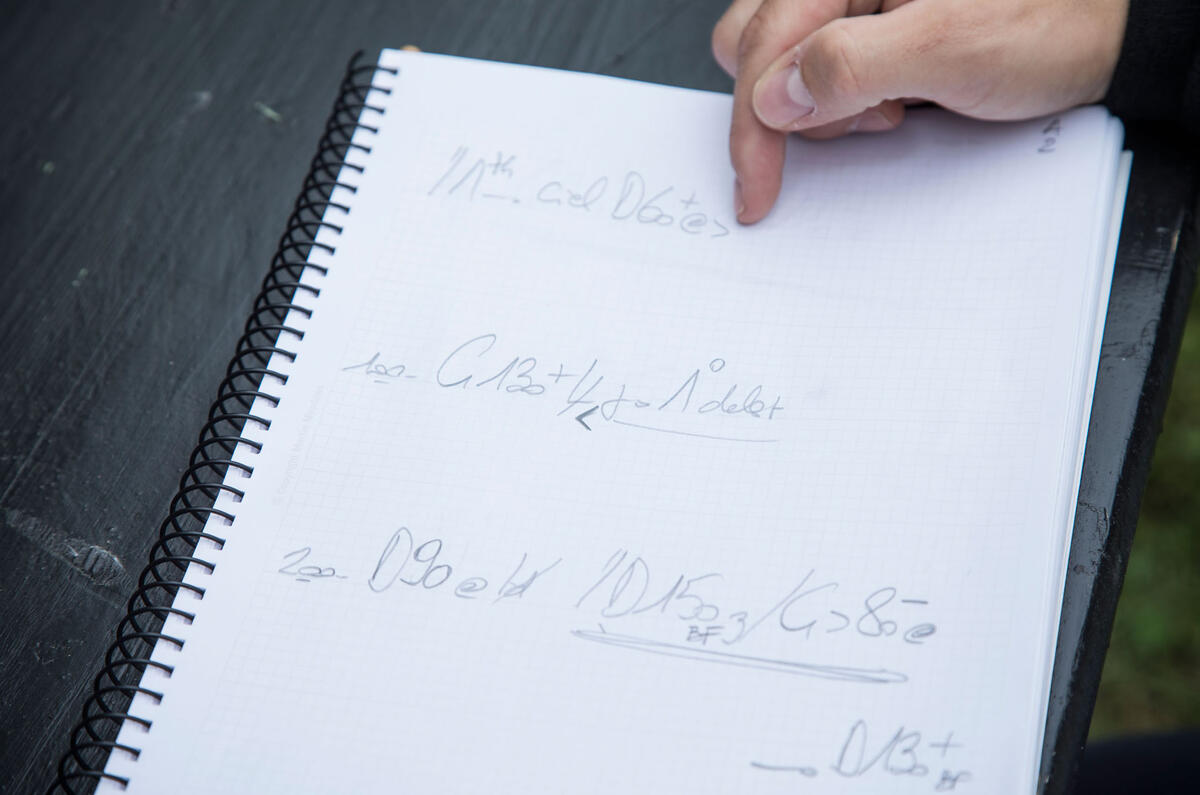

At WRC level drivers get to recce the stages before the event to make pace notes, and making accurate descriptions of the jumps is of paramount importance.

“You have to have very good pace notes with your co-driver from the recce to help you get the car on the correct line before you go over the jump so you can land on the right point afterwards. Especially when there are corners straight after the jump, because you want to land on the right line into the apex,” says Neuville.

The driver can only do so much, though. Suspension settings are key to jumps, and that’s what helps the car land flat without bouncing. Neuville’s Hyundai i20 WRC may bear some resemblance to the road-going version, but that’s where the similarities end. The 300bhp rally car features a host of changes, the main ones being stronger, oversized competition dampers and a more rigid chassis with a roll cage.

Add your comment