f you only read headlines, you could believe UK Automotive Manufacturing Plc’s entire business (still healthy despite the predictions of doom) was conducted entirely by car makers and giant parts suppliers whose names are carried three metres high on factory walls.

That’s not quite true. Below the radar sits an extensive network of discreet technical consultancies the majors commonly use to solve their thorniest problems. They survive and thrive by maintaining a limpet-grip on leading-edge technology and delivering results with a need-for-speed usually honed in motorsport.

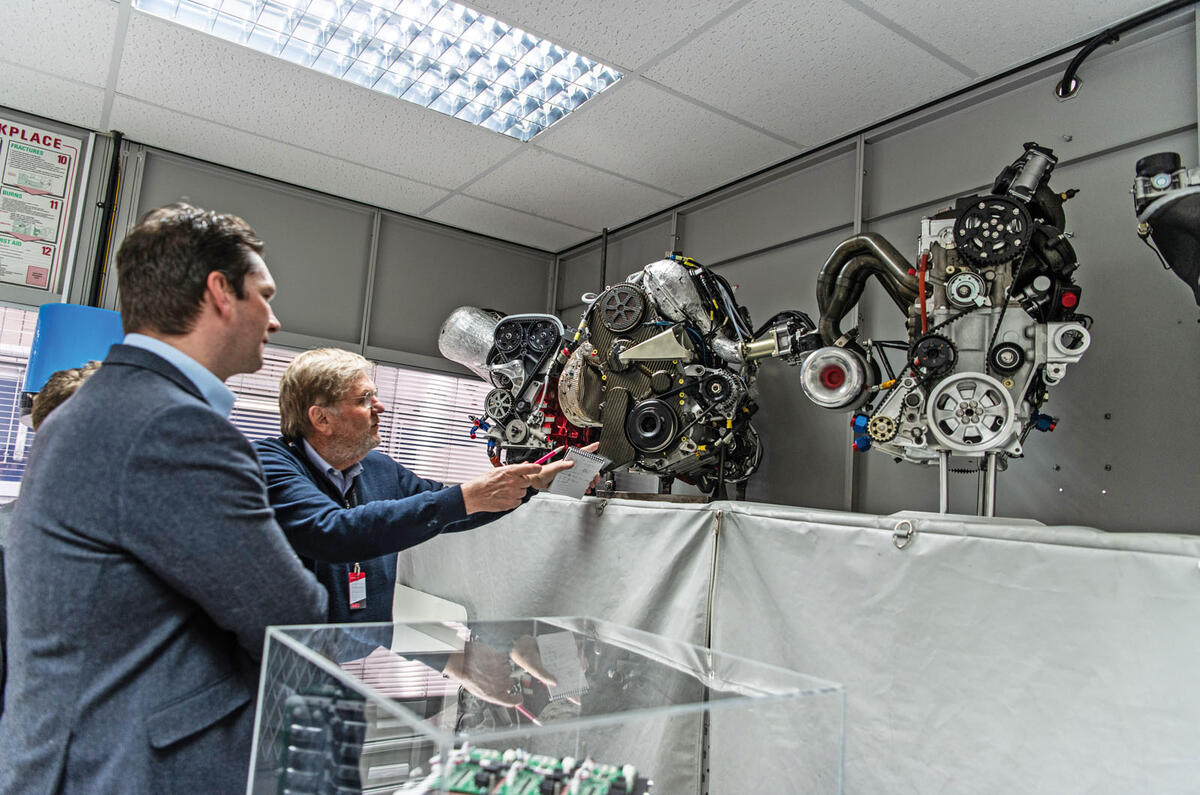

A prime example is Northants-based RML Group, an engineering and technology company with racing roots back to the 1950s and which expanded into top-level race car design and engineering in the 1980s. It has since further expanded its activities to become a leading authority in lightweighting, prototype construction and electrification, mostly for time-poor automotive giants but also for defence and aerospace clients. Sitting atop this compact empire in Wellingborough, Northants, is CEO Michael Mallock, grandson of Arthur Mallock, an architect of Britain’s post-war motorsport engineering heritage that spawned influential companies such as Colin Chapman’s Lotus and Eric Broadley’s Lola.

But while Chapman & Co embraced commerce, Arthur Mallock kept making simple, affordable cars go amazingly fast. His Ford and Austin-based specials regularly beat far more expensive and complex designs; his finest hour was probably the creation of the U2 family of clubman race cars that applied basic physical principles so brilliantly that they remain highly successful in modern and classic racing even today.

It fell to Arthur’s sons, Richard and Ray, to develop businesses off Arthur’s inspiration. Richard’s stayed with Mallock’s racing cars and Ray’s expanded into RML Group – embracing big-time racing and engineering. It built and campaigned BTCC cars and Le Mans racers (Ray’s special love) before expanding to become a self-styled ‘high-performance engineering company’.

Add your comment