With the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) and electric vehicles dominating the news, many see synthetic fuels (e-fuels) as an alternative solution to reducing transport emissions.

Clearly, with ICE cars continuing to be driven beyond 2030 and indeed continuing to be sold up until that point, there needs to be a broader answer than simply a route-one electric fix. But are e-fuels really the solution?

In the latest Autocar Business webinar, we were joined by Paddy Lowe, an ex-F1 engineer and founder of Zero Petroleum; Christian Schultze, director of technology research at Mazda Europe; and Steve Sapsford, managing director of SCE, a consultancy firm specialising in sustainable fuels.

What exactly are e-fuels?

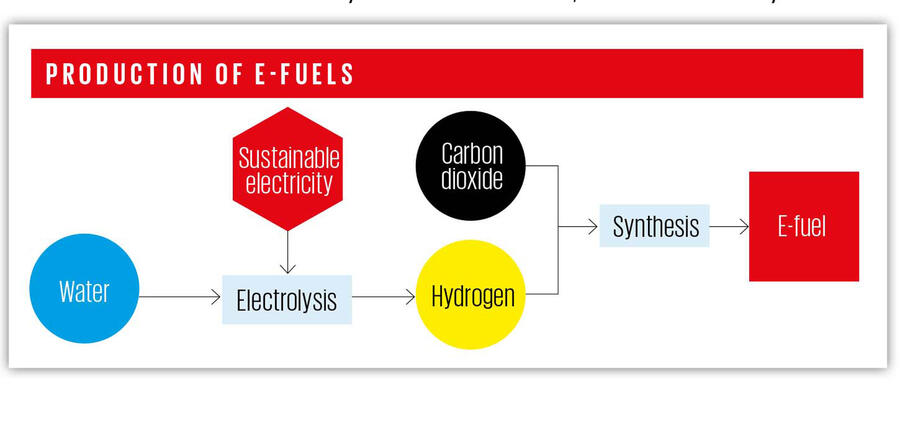

PL: “E-fuels have various names. We actually prefer to call them synthetic fuels at Zero Petroleum, because we thought it’s a more generic name. It’s more user-friendly to the public at large and ‘synthetic’ means made by man, rather than by another process. So in particular, what distinguishes e-fuels from other sources of liquid fuels – biofuels, for instance – is that synthetics are industrially made and they don’t require the use of agriculture. They gain their energy from a renewable source that’s industrial, rather than coming via the biology of a plant.”

SS: “I use ‘sustainable fuels’ to be the catch-all for everything. So I’ve got biofuels under there as well as synthetic fuels. E-fuels are a special version of synthetic fuels that use renewable electricity to generate the hydrogen.

What we need to think about is how effective each of those types can be as time moves on. Some of the synthetics and particularly e-fuels aren’t available in large quantities at the moment, whereas the biofuels are available in much more significant quantities. So I expect to see a shift in use from biofuels through to synthetic fuels over time.”

What does this mean for a major OEM like Mazda?

CS: “We have to find a solution to become climate-neutral, because this is also one of our commitments, by a way that’s compatible to the region. We see different approaches. In Europe, electrification seems to be the major way, but we believe it’s maybe more healthy and faster and safer to take a more technology-open approach. We call it a multi-solution approach to fit the best technology for the people in each region.

“E-fuels aren’t in competition with the electrification route. With having two pathways to follow, we believe we can assure better and faster to reach climate-neutrality.”

Join the debate

Add your comment

There is not one mention in this article about air pollution, one of the most serious by-products of internal combustion, which kills thousands of people a year just in the UK. This pollution would continue if internal combustion cars were converted to burn synthetic fuels. In fact, the latest research quoted by Transport & Environment proves that NOx emissions from synthetic fuels are the same as from fossil fuels. So synthetic fuels are not the answer, even for existing IC cars. Far better to convert them to battery electric, as is already happening with many classic vehicles. Faster, less polluting and more reliable, what's not to like?

We have a huge legacy fleet of vehicles, where the carbon cost of manufacturing them has already been expended but instead of finding ways to power them with an eco friendly sustainable fuel, we're all being encouraged to commit them to the scrap heap, waste more resources on a new vehicle and even more installing the infrastructure to make it run.

Even recycling our current vehicles has an environmental cost, so surely it's better to retain and improve the existing fleet of ICE vehicles or at the very least, continue to utilise the existing infrastructure to distribute new synthetic fuel?

Other technological answers, like Transient Plasma Ignition could help reduce ICE emissions and be retrofitted but all the politicians are too busy lining up deals to make their mates the next 'e-Billionaires', to listen to alternatives.

With the best will in the world, we're not going to completely replace our existing vehicle fleet for at least 20 years, so it makes total sense to develop more sustainable synthetic fuels that we can start using soon. And who knows, there may be a demand for such fuels for many years to come to power aviation, shipping, HGVs, sports and competition cars. If we are to decarbonise our transport system, then we are going to have to pursue many solutions, not just the battery solution currently favoured by politicians.