One of Britain's most advanced vehicle factories, owned by EV start-up Arrival in Bicester, is nearing the day of making its first parcel-delivery van, and Autocar has enjoyed an exclusive first look.

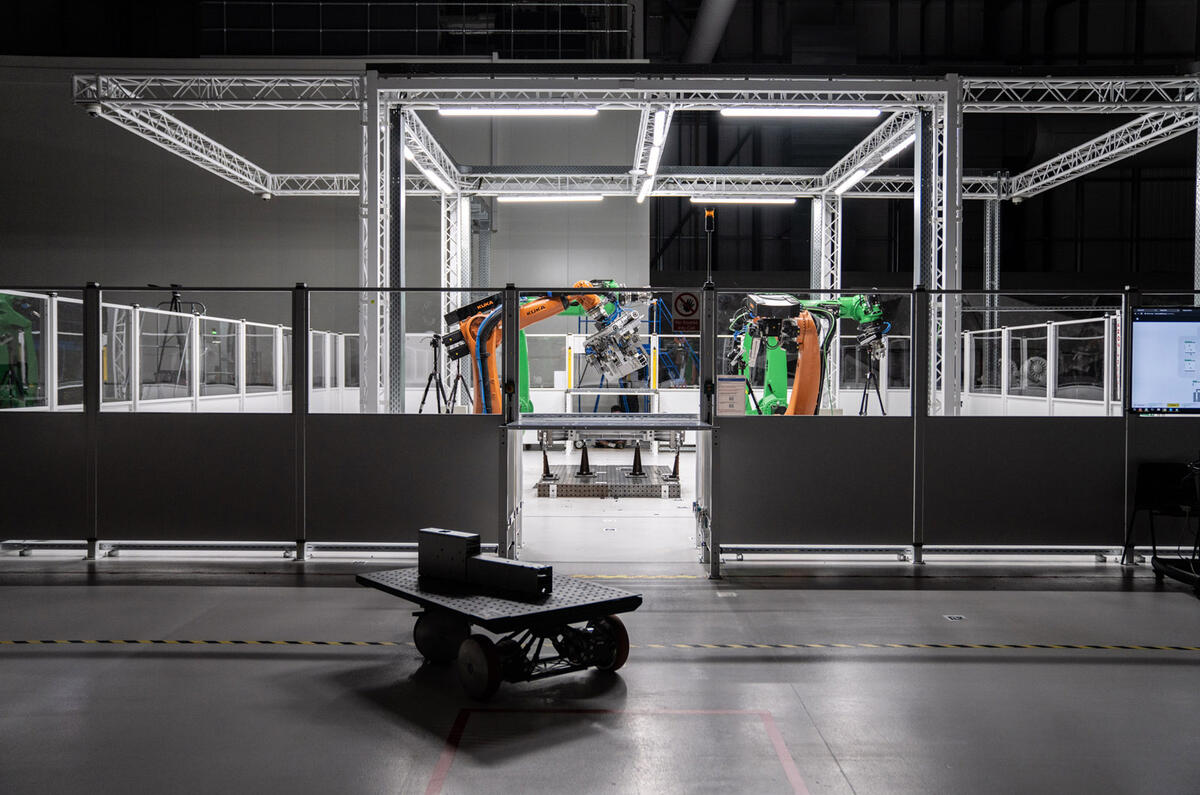

The site is the first in the world to use a ‘microfactory’ production system, in which a usual assembly line is replaced by flexible manufacturing cells, with the design, layout and low output of the site established for supplying the local market.

Join the debate

Add your comment

While this is most interesting and using light vans makes sense there is no evaluation of the total energy needed to manufacture theses vehicles. If we are to live , or our grandchildren, in a low emission world total energy and lifetime use of energy and recycling energy has to be stated.

While this is most interesting and using light vans makes sense there is no evaluation of the total energy needed to manufacture theses vehicles. If we are to live , or our grandchildren, in a low emission world total energy and lifetime use of energy and recycling energy has to be stated.

While this is most interesting and using light vans makes sense there is no evaluation of the total energy needed to manufacture theses vehicles. If we are to live , or our grandchildren, in a low emission world total energy and lifetime use of energy and recycling energy has to be stated.